Finding Meaning in The Nature of Order

A cognitive-scientific perspective on Christopher Alexander. My presentation at the Building Beauty Nature of Order webinar — video and transcript.

Last week I presented at the Building Beauty Nature of Order webinar. This week I’d like to share the recording with you, and I have also transcribed my presentation (without the Q&A that you can find in the video).

What follows is the transcript of my presentation, slightly edited for readability, and without the introduction and Q&A that you find in the video.

Transcript

Hi everybody. I’m Stefan. I’m calling in today from London, UK, which is where I live. I was a Building Beauty student in 2020/21, where I went through the program. But I am a software-engineer. I don’t have that much to do with architecture in my work life. And I’m also not really a cognitive scientist.

Nevertheless, I’m going to talk a lot about very basic cognitive science today, because that’s what I spent quite a bit of time with in the last few… I guess I can say years now.

This is a quote from The Nature of Order that I want to begin with:

“I wanted to be able to do the real thing — and for that I had to know what the real thing is.

The reason was not intellectual curiosity — but only the practical reason that I wanted to be able to do it myself.”— Christopher Alexander

This is kind of how I'd like you to frame this presentation today. Even though we are talking about science, we are talking about very “head-y” things.

Ultimately, I also want to be able to do it myself — in my case it’s less about building beautiful buildings, and more about building beautiful software.

But as I was trying to figure out what the real thing is, I discovered cognitive science.

Cognitive Science

Just a quick refresher on what I mean by cognitive science here:

Cognitive science is not like one of those things here, it’s basically all of those things that I listed on this slide. Cognitive science involves all these different scientific fields, but it is not just an umbrella term for them — it is about the deep integration of those fields. It’s not just about being a psychologist, maybe, and then citing a paper from linguistics. That’s not necessarily cognitive science. Cognitive science is to take input from all those fields and try to connect it to other fields and generate insights from the combination of those.

4E Cognition

The cognitive science that I looked at is more specifically the cognitive science that’s known as 3rd generation cognitive science, also called “4E cognition”. And the four “E” stand for:

embodied

embedded

enacted

extended

But mathematics — as you’ve just seen on the slide before — was not part of the list, so because cognitive scientists are not mathematicians, it also sometimes stands for:

emotional

emergent

And you might hear about “6E” cognitive science these days as well.

Unfortunately, I don't have the time to go through each of those words and explain why that is so important to cognitive science. But for this group here in particular, who is also interested in Alexander’s work, I think a way to look at this is this:

Alexander criticizes the Cartesian, scientific, mechanical worldview, because it doesn't offer any ways to explain human experience. Guess what, a lot of cognitive scientists agree with that. And they came up with different, still scientific models that integrate human experience — us as experiencing individuals — into the model of the world, without leaving behind this idea of a shared reality that follows certain rules. So this has nothing to do with subjectivism, where everything is experience or imagination. All the physics that we’ve figured out is still valid, still applies, as part of our shared reality. But in addition to that, cognitive science also integrates our personal experience into that worldview, so we are not just independent observers anymore.

"Embodied cognition" is — to a certain extent — a scientific realization of the "modified picture of the universe" that Alexander talks about in book 4. It’s probably closer to what he called the psychological explanation, which he deemed inferior to his physical explanation that he talks about in book 4 as well. But I think it’s still a very helpful model to look at.

The other thing that I want to say, just to make sure that we’re all on the same page, I'm not here to give a scientific "proof" of the correctness of Alexander's theory in The Nature of Order or anything like that. Apart from the fact that I wouldn’t know how to do that, I'm not here to give you scientific reasoning on why you should believe in what Alexander says is true (or false).

The thing that I want to do today is just to provide you with a few basic concepts that I picked up as I was studying cognitive science, that I found useful to make sense of concepts Alexander talks about. And I hope that these will give you additional perspectives on The Nature of Order and perhaps offer some insights.

And with that let’s get into it. There will be five sections. The first one is about knowing.

I. Knowing

How do we know the world?

This is a little bit connecting to what we had last week [where we learned about and discussed Iain McGilchrist’s two hemisphere model].

Here are a few potential answers to this question of how we know the world. And you can see already that I arranged them in a certain way. If you’ve been here last week, you know where this is going.

On the left we have "science-y" stuff, "hard scientific truths", which are often quite removed from our personal experience and very abstract.

On the right we have that "touchy-feely” stuff. We might not understand it fully scientifically, but we all have certainly very strong personal experience with those things.

Regardless of which parts of our brains are responsible for which of those, I think we can agree on that there is a fundamental division between them — if it’s not in the brain, it’s definitely in our culture.

There is this deep divide, and what we usually do is we tend to emphasize the things on the left. And this is of course what Alexander criticizes with the Cartesian-mechanical worldview. Last week we heard about McGilchrist, who talks about left-hemisphere dominance, which I think is the same concept. And today you are going to hear about John Vervaeke, a cognitive scientist who calls this “propositional tyranny”.

Why does he call that "propositional" tyranny?

4 Ways of Knowing

Because he thinks that there are four ways of how we can know the world. Let’s have a look at those.

Propositional knowing

The first one is propositional knowing. And this is about knowing what, knowing that something is the case. You memorize propositions or facts and store them in semantic memory. Things like: A cat is a mammal. These kinds of very simple relationships between things. This is the kind of stuff that was on the left side on the page I showed you before.

These facts that you store in your memory turn into beliefs and theories that you can write down or communicate to others through language, which enables cultural preservation of knowledge and collective intelligence. So there's nothing bad about this in general. There’s nothing bad about propositional knowing inherently.

But in order to know how to seek the relevant information, how to come to those facts, in order to know how to ask questions, or how to argue with other people about things, or how to propose theories, we need skills.

And this is what procedural knowing gives you.

Procedural knowing

This is knowing how to do something. You practice sensory-motor interactions and you store them in procedural memory. Examples are: Riding a bike, throwing a ball, kissing someone you love, these kinds of things.

These interactions become skills that you can apply to interact with things and other people in your environment.

Now in order to know which skills to apply in which situation or which ones to learn, if you notice that you need to learn something, you need to be aware of the situation that you find yourself in.

This is something that you get from perspectival knowing.

Perspectival knowing

This is knowing what it's like to be you, here, right now. You inhabit or embody a perspective and this is something that you store in episodic memory, so you can recall episodes. You probably know what you did on your last birthday and you can recall that from your episodic memory.

A perspective is a certain state of mind which makes things in your environment stand out to you. There are certain things in your environment that you pick up, and there are other things that are more backgrounded, that are not important to you right now. It kind of guides your attention. Vervaeke calls this a salience landscape, so you have a landscape in your mind, where there are things in your environment that are standing out to you, they are salient to you, or they are not. And this depends on which state of mind you’re in. This is something that gives you situational awareness.

Think about it like this: The very same environment without any changes appears very different to you, depending on which perspective you currently inhabit. For instance, if you're hungry and you walk through a supermarket, other things will stand out to you, than if you walk through the same supermarket and you’re not hungry. Or if you’re in a discussion and you’re angry about something, you will probably listen to what is being said in a different way than if you are not angry. This is what’s meant by perspective here.

Think about how this concept helps already explaining or better understanding why it is so important to be in a certain state of mind, when you’re trying to identify centers in your environment.

But in order to have situational awareness, what else do we need? We need situations.

And this is what participatory knowing is about.

Participatory knowing

A situation basically just means: How are you situated in your environment, how do you fit into your current environment?

The environment has been shaped in a certain way, so you fit to it in a certain way. Through physics, biology, evolution, and culture, all these things over time have shaped you and your environment so that you fit together:

For instance I have a cup here. The cup is graspable because it has a handle. We came up at some point with this idea to put a handle on this because we can use our hands, and then it’s easier for us to deal with this. Or the floor has been shaped so that it’s walkable with your bipedalism, because we are adapted to walking on flat surfaces.

You fit together with your environment, and you have all these affordances that come out of that, so you can meaningfully interact with that environment. And this is what’s meant by being an agent in an arena.

When the role that we assume for ourselves in this particular environment fits that environment, that means we are able to act appropriately.

Imagine you are a football player in a football stadium. You know exactly what to do. Everything makes sense: the ball, the markings on the field, the goals; they all have certain meaning for you and this meaning is clear to you. And in that situation everything around you has basically been designed so that it makes sense to you, and you know exactly what the relevant objects are in your environment at that point in time, and you know how to interact with them. In this case you have a very good coupling to your environment, you have a functioning agent-arena relationship.

I want to go a little bit deeper into this.

Agent-arena relationship

The way this works and the way this is set up is: You are the agent and you assume an identity for yourself. But you also assign identities to objects in your environment, your arena. These identities depend on each other and they need to match up. The identity you assume for yourself depends on the arena that you're in. But at the same time the identities that you assign to the objects in your arena depend on your identity as an agent. They are co-identified.

The things in your environment do not inherently have a particular identity that you pick up on — it’s not purely objective. But also, on the other hand, you’re not just making up identities for them either — so it’s also not just subjective. It's kind of both at the same time, but this is a little hard to explain. Vervaeke calls this transjective, because it transcends this dichotomy of subjective vs. objective. We do not receive these identities from the environment, and we do not purely assign them ourselves, we kind of participate in this process of making these identities happen.

I made it sound very active, but this is obviously something that happens very deeply subconsciously, we don’t really have access to this mentally. It just happens. And it’s even pre-conceptual, before we have concepts in our minds. By the time you realize a thing as a thing, this has already happened. This is something that’s required for you to make sense of objects around you. This is also something that’s required for you to perceive you as your self, this is your own identity.

This is all based on a framework called relevance realization, which I would really love to go into, but we absolutely do not have the time to go that deep into it. Maybe there is some place for questions later.

Ideally, in this agent-arena relationship you have good coupling, so everything in your environment makes sense, or maybe not everything but you feel comfortable there, because the way you interpret your surroundings is appropriate and the feedback that you get from it as you interact with your surroundings makes sense. It is the feedback that you would expect. You fit together in that situation. It makes sense.

If you do not have good coupling, then you feel like you’re out of place. You feel like you do not belong here. Things don't make sense, and you perhaps don't even know what to do. Imagine if you’re a football player, but you are on a tennis court — that doesn’t make any sense. Everything is weird, it's even absurd. That’s the kind of situation that you could be in, when you’re missing a good coupling, when you’re missing a good agent-arena relationship.

This concept of agent-arena embedded in this whole idea of participatory knowing relates really well to what Alexander calls “belonging".

Here are all the four ways that I just talked about on one slide together.

As I already pointed out as we were going through them, they all rely on each other, they’re not independent. They are very connected to each other.

Each of those also has a different sense of realness, which means that the different kinds of knowing give you a different feel for when something seems more real to you:

For instance, for propositional knowing beliefs are real, when they are true. That’s very simple. Your sense of realness is truth.

For procedural knowing, skills give you power. Because when you know which skills to apply and how to apply them well, then you feel empowered in that situation, and that feels more real to you.

Situational awareness from perspectival knowing gives you presence. When you are very present in the moment — think of being in the flow state — your situational awareness effortlessly selects the things that are relevant to you in that situation from your environment so you know how to act appropriately. Often people when they are in flow report that they weren’t thinking, they just knew what they needed to do. And this is what feels more real to you.

And finally with participatory knowing, if you have good coupling of agent and arena, you feel like you belong there. You fit into the environment, and you have lots of affordances, lots of options of how to act in that situation. You feel deeply connected — you feel belonging.

Notice how this sense of realness across all those types manifests in many different ways, but all of them have to do with how well you are connected to reality.

And think about how important a sense of power, presence, and belonging (the lower three parts of this) are important for your existence. None of those four ways of knowing is more important than the other. Your sense of realness, your sense of meaningful existence is profound when they all work together optimally.

If you see how important power, presence, belonging (the lower ones) are for your meaningful existence, it makes me wonder sometimes why we still try to reduce everything to ideology, to propositions and beliefs in them, which is purely propositional. And this is why Vervaeke calls this propositional tyranny, which is what we seem to do these days.

As you can see from this, when we think back of what I presented earlier, the two sides with left and right… the things on the left, objective knowledge, intellect, reasoning, that kind of stuff, this is all in propositional knowing.

And the subjective experience on the right, intuition, emotion, that kind of stuff, this is basically in the lower three, in the non-propositional kinds of knowing. We could probably try to figure out which goes where, but this is also I think beyond the scope and time that we have for today.

What I like about this model is that it works with that division that we talked about last week and in the beginning today with left and right. But it differentiates it even more, gives us even more detail, but then it doesn't stop there and leaves us with figuring out what to do with that now. It integrates everything back together in this model where everything is dependent on everything else. It avoids this polarization that you want to immediately say, “Yeah, propositional knowing is bad and this other thing is much better.” It’s more difficult to fall into this automatic pattern where one of them is suddenly the bad one and the others are the good one.

And I think we can also see that there is a deep continuity between the top and the bottom, between our most abstract conceptual abilities at the top — the propositional; what we would conventionally call knowing — and our most embodied sensory-motor interactions and experiences at the bottom — which are closer to what we would consider being.

II. Being

Being is, as I just explained, ultimately participatory and it’s about our relationships — our transjective relationships with the world, with others, and with our selves. So how do we relate?

And here I want to introduce you to a theory from German psychologist and sociologist Erich Fromm. He talked about existential modes.

Existential modes

When these agent-arena relationships are formed subconsciously, where we assign identities to objects but also assume a certain identity for us, there’s one factor that plays an important role in how these relationships turn out. This is the existential mode that we're in. Fromm talks about two of those modes:

Having mode

The first one is the Having mode.

When you are in the having mode, you understand these relationships with things in your environment in a categorical way. That means that you classify things and you categorize them so they belong into a certain category, which is some sort of generic identity.

I have a cup here. This is a cup. There are many cups. I treat them categorically. If this one breaks, I just get another cup — it's replaceable. I also use this cup to drink from, because it makes drinking easier for me. If I wouldn’t have the cup I would have to use my hands and that would be very messy and very difficult. It’s great that I have a cup because it solves a problem for me.

And this is what the having mode is all about. It enables us to control things, to manipulate things, to replace things. Our relationship is possessive. It affords us to solve problems and is very result-oriented: The cup solves my problem of being able to drink. It’s very results-oriented in the sense that it’s closed, it’s convergent towards a goal, and it’s all about effectiveness and efficiency.

That means that generic, mass-produced, replaceable products are useful, because they solve problems for us. But of course, we don't necessarily feel a particularly deep connection to those things.

As a software person I’m always a little bit shocked how deeply the having mode characterizes our efforts.

But there is also the Being mode.

Being mode

The Being mode is very different. In the being mode, we understand our relationships as developmental. We want to become something, we want to transform ourselves. We want to grow.

It is very process-oriented: We interact with our environment and we discover things about it. We engage in mutual disclosure, where we are in an open, expressive, and exploratory relationship. We’re not trying to solve problems in this mode, we are discovering and making meaning.

Think about it like this: Things that you truly love are unique and irreplaceable: individual people, unique places, even special things that over time have for some reason become very special to you.

They have an identity that is very specific. It’s not a generic, categorical identity. There is only this one thing, and it’s not replaceable at all. And this means we can meaningfully connect to this thing or person.

A summary of those two modes would be: One the one side we have meaningless havings, and on the other side we have meaningful beings.

Modal confusion

There is, of course, a problem with that. And the problem is not that the Having mode is bad and the Being mode is good. That’s too easy, that’s too simple. It is that our culture is built around the Having mode. That is the problem.

If you look at what’s culturally important to us these days: It’s about control, generality, efficiency, scaling, cost — all these things that count in capitalism are very Having mode-ish. Or I could also call it System B, probably.

For instance advertising is a good example for how this plays out in the world. Advertising constantly tries to convince us that we can meet all our being needs to grow and mature within the having mode by just spending money on something. You want to become more beautiful, buy this shampoo. You want to become more intelligent, take this course.

We have designed our culture so that there are huge incentives to keep us in the illusion that we can satisfy our developmental being needs in the Having mode.

What we need to do is, we need to remember the Being mode. And I think that is ultimately what Alexander is… he doesn’t call it that way but I think Alexander is helping us a lot with remembering the Being mode.

Reciprocal realization

One of the features of the being mode is something that I… I mean, not I, but the people that I read a lot about, call reciprocal realization.

Think about it like this: As we change the environment, the environment changes us. Or in more detail: You change something in your environment, and that change then has also an effect on you as you perceive the changes that we just made. You respond to that by also changing yourself. And then we make another change. There's a feedback loop that’s starting. Does that sound familiar?

When we respect, preserve, and enhance the uniqueness of a place, we are shaping its identity, so that it becomes more special to us. As it becomes more adapted to us, we also respond differently to it — we are changing too. We are growing together, we are making meaning together.

If you think of the environment — and this is going to sound ridiculously technical, but bear with me — if you think of the environment as a person that you interact with, perhaps even a person that you have an intimate romantic relationship with, then this reciprocal realization, you opening up to them, disclosing something about yourself, and then they reciprocally opening up to you, disclosing something about themselves, and this process repeating, with both of you learning new things about each other and in this process together transforming each other, growing together — that's love.

It's an open-ended, process-oriented, ideally over time intensifying, deeply meaningful relationship that you build, where each of you grow, together. It's a journey of becoming, where it's all about the journey and not at all about the destination.

And it seems to me that Alexander has made similar connections:

"That kind of adaptation makes them lovable, and possible to love; and when we love them, we belong there."

— Christopher Alexander

I’d say that we could re-interpret parts of the fundamental process that Alexander talks about as participating in a being-mode relationship with our environment, where we grow together through reciprocal realization, becoming more and more unique and meaningful to each other, such that we start to feel deep belonging.

We’re almost talking about making already…

III. Making

What’s this? What do you see here?

If you think that’s a bird then that’s what was intended. But how did you know that this was a bird? What makes a bird a bird? Some strange basic philosophy question here.

One way to answer that question: We could come up with a feature list. A feature list for birds:

has two wings

has feathers

has a beak

can fly

Maybe it’s not complete, but that is a pretty good description of what a bird is, right? The question is: Is that enough?

Is that enough for us to understand what a bird is? Can we understand something just by having a definition like this? By having a list of its necessary and sufficient features? Do we understand something, when we can describe it?

When you looked at this picture that I just showed you, I hope that now in hindsight you are aware that you were probably not thinking about features at all. You were doing something that’s called gestalt perception.

Gestalt perception

You know what a bird is, without thinking about its features. You just have a sense for it, you just sense its gestalt without thinking about it. Your grasp is immediate and intuitive, and not analytical at all. That can come later if you want it to, but you just knew it.

Your knowing what a bird is is deeper than just on the propositional level or on the language level. You don’t have to think in its parts to figure out what it is, you can think in wholes. Your ability to describe features then rests on top of this deeper, intuitive knowing. Because once you figure out that this is a bird, then you can think about what actually makes it a bird, and then you can jump into this propositional figuring out what the features are that you should put into a feature list.

The cognitive concept behind this is gestalt perception, which means that we can sense something, which is the pattern or configuration or structural-functional organization of the thing. Basically, how the parts are structured together so that they function as a whole. And we can instantly pick this up, if we are familiar with this thing.

The feature list misses all that. The feature list does not have the organization, an arrangement, a structure, geometry, order. They are not part of the feature list.

This is what I think makes the whole greater than the sum of its parts. It’s that we have that ability to feel a little bit more than just having a list of features.

As a software person I have this feeling that we don’t really buy into this “the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts”, because every time we are in a situation where we feel like that, we start looking for the missing piece, because clearly there is a part that’s missing, that we need to find so that we can go back to “the whole is exactly the sum of the parts”.

Features + Gestalt

We can define parts, but we sense the whole. We can give an analytical description of features, but we have an intuitive grasp of the gestalt.

You can see that they are at the opposite ends of the spectrum of knowing.

We can stand apart from something and we can describe it from a distance by just looking at it and making propositions about it, and perhaps change our beliefs about it. But we stay independent from it. We are not in touch with it. That’s one way of describing a thing.

Or we can take the same gestalt in our mind, participating in it, but also with our body. My favorite prop these days, this cup… when I use this cup I’m changing my body, I’m grasping it, changing my body to the shape of this. Even in my body I’m having this intimate, complex, sophisticated sensory-motor interaction with it — and this is by the way what embodied cognition is all about. The way we interact with something, is an important part of how we understand it. It’s not just looking at something and figuring out patterns, it’s very much connected to the experience that we have interacting with something.

We change our own structure to know the cup. We transform ourselves in order to know the thing. We’re not just changing our knowing, we are changing our being. We know it by con-form-ing to it.

Form

When you think about the form of something… and this goes back to Plato. Plato was writing about this using the word “eidos”, which has been translated in many different ways. One of them is form, another one is shape, which is probably not the most accurate, or formula. And you can tell already from the challenges that we have describing or translating this, he is describing a concept that’s very hard to describe with words but it’s very obvious if you just think about your personal experience with it: We know what something is without using words, we just know it. And this is I think what this is about. The closest being the gestalt of it, or this form.

What Plato meant is that you have in your mind the same real form that's also in the thing, because that is ultimately what allows you to come to know it.

When we grasp the eidos, the gestalt, the shape, pattern, formula of a thing, we con-form to it, we are participating in its form. When we grasp the gestalt of a bird, we understand what a bird is. That does not mean that we can then automatically accurately describe it. It turns out that that is actually pretty difficult.

This way of looking at knowing and looking at form suggests that there is no real distinction between knowing and being, that knowing and being are much more integrated.

But I said this part of the presentation was supposed to be about making. So let’s ask this question: Who knows a thing better, a person who can describe it, or a person who can make it?

A describer seems to be able to get away with just a feature list or a definition. But if you want to make something, I think it’s pretty clear that you need to be familiar with the structural-functional organization of the thing. You cannot just know the features, you need to know how those feature go together. You need to have this eidos in your mind.

Here’s a side question for software people: Are we really making, or are we just describing?

Aristotle took stuff from Plato and was interested in the process of how things become other things — the process of development or growth. And he came up with this interesting distinction between actual and potential.

Actual & Potential

Here’s my very nice picture to make this point clear.

Let’s say you have a block of wood, and you could potentially make a chair from it. Or a table (it’s a big block of wood). Or maybe a bed.

The block of wood represents potential. When you shape the wood in such a way that it can act as a chair, when you take the eidos of a chair in your mind, and you in-form it into the wood to actually become a chair, then you have actualized potential. You have turned potential into an actual thing.

Basically, you caused a chair to be, be-cause you deeply understand what a chair is. If you take the eidos of a thing in your mind and you actualize it in some potential, you can make an instance of the thing.

Look at what’s going on here: When you shape the wood to become a chair, what you’re shaping is its form, you’re shaping actuality, so that it acts like a chair when you’re done with it.

But then look at what happens next: What you’re also doing is… the chair has a function. You’re also shaping a function — this is the possibility of future events. Now you can sit on the chair, which is something that wasn’t possible before. Whenever you create something, you’re shaping actuality, but you’re also shaping future potentiality.

This is all a very abstract and long-winded way of saying something that the students here have probably heard in the studio classes many times, which is:

“To really understand, you need to make it yourself.”

I think this explains quite well why that is the case.

You need to participate in a deeper way, not just having a description of it, you need to participate in the same form, you need to be deeply in touch with it. And a great way of doing that, is making it.

This means you basically establish this intimate connection between your mind and reality. You bridge this big divide we talked about in the beginning. You’re finding a bridge here, that bridges this divide, where you take your mind and what’s in reality and you find a good, useful connection between them.

How you make sense of a thing, the pattern of intelligibility, is the pattern by which it is organized and how it is structured and how it functions. For this kind of deep understanding, you need to be deeply in touch with it. There is not really a distinction between knowing and being here.

Knowing = Being

Deeply knowing something in this way does definitely not just change your beliefs, it changes the structure and functioning of your own being.

I think Alexander's theory of centers is very much aligned with the idea of eidos, or structural-functional organization. And perhaps when he talks about our sense for wholeness, all these ideas that I was just talking about, about form, gestalt, and conforming in a participatory relationship are quite useful concepts. If we consider the act of making as causing something to be, it might even help us understand how strong centers eventually can become beings.

IV. Becoming

Let’s talk about living things. But first in the boring biological sense.

This is a tree, just as an example. Think of a tree as a living thing that is self-making. The tree makes itself. How does it do that?

It’s basically growing in a certain way. It tries to grow towards the sun. It wants to expose its leaves to sunlight, because that’s where it gets all the energy and resources from to grow. It wants to maximize the chance of photons hitting chlorophyll molecules.

The tree is self-organizing in that way, it’s self-making. There are events that happen, photons hitting chlorophyll for photosynthesis to happen. These events happen that cause the tree's structure to change, because that is how the tree grows, how it finds the energy and the material to grow. And then the changed structure constrains future events. If the tree grows successfully, then it will increase the chances that there are more leaves that are now exposed to the sunlight. There is a little bit of this reciprocal realization thing going on here with the environment.

You could also say that the tree self-transforms to become better adapted to its environment. And at the same time it also preserves its structure to still be a tree. This is definitely a structure-preserving transformation.

This is an interesting way of understanding development or growth: Events cause structure to change. They actualize potential. But then the changed structure constrains future events, it shapes future possibilities — it shapes potentiality.

I want to look into the constraints a little bit more, because there are two types of constraints. We are probably more familiar with the second one, that is probably what we first think of, when we hear the word “constraint”.

But there are actually enabling constraints that are making events more likely, they open up the system, they create options, they create variation. There’s a divergence that can happen, because there are many different new options.

And then of course there are selecting constraints, which is kind of the opposite. This is probably what we think of when we hear the word “constraint”. It makes things less likely, it closes down the system, it reduces options and reduces variation, and it cases some sort of convergence to something.

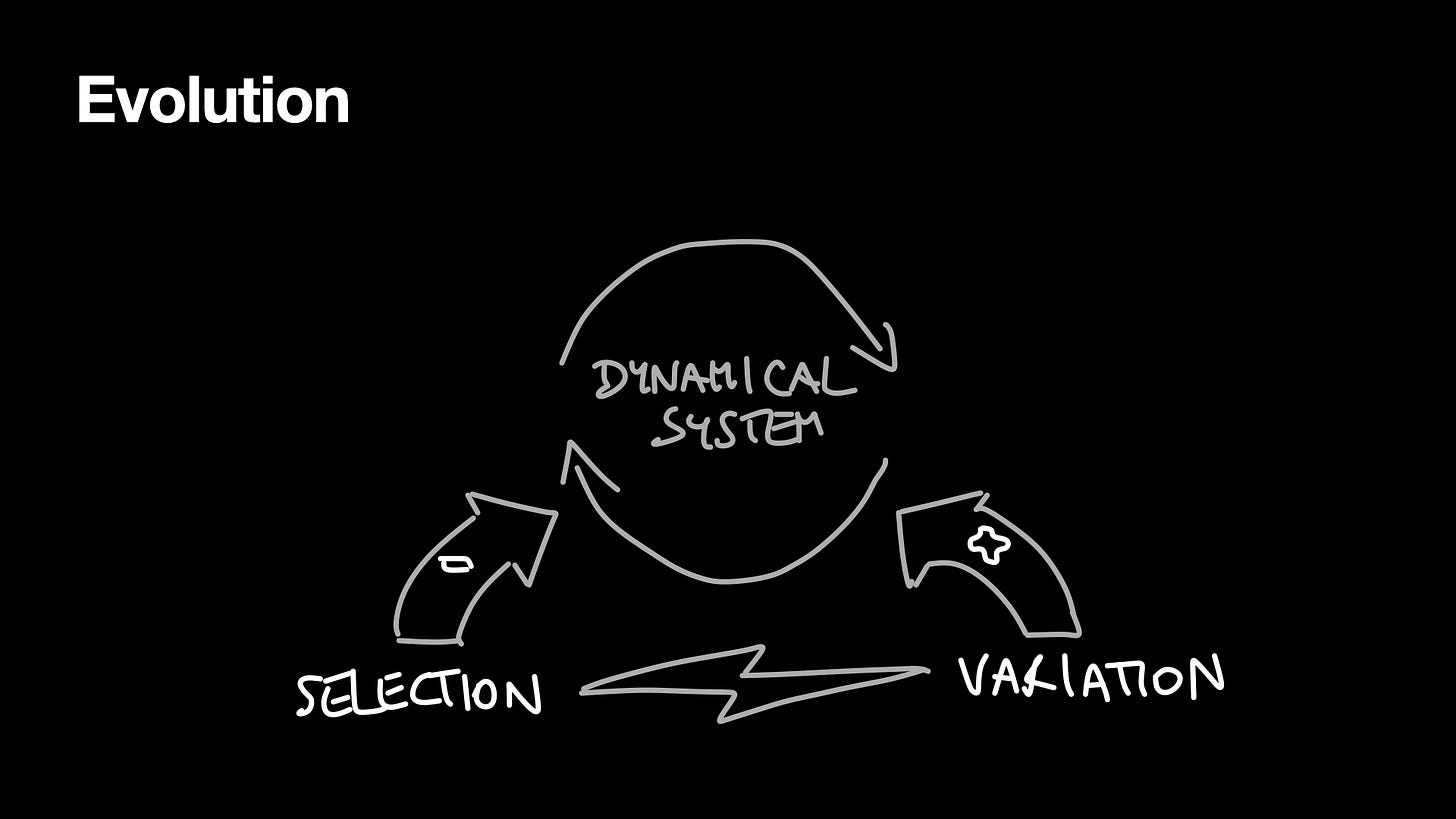

We’re deep in dynamical systems theory already. And the first dynamical systems theory probably is evolution.

Evolution

Instead of looking at a single tree, we zoom out as far as we can and we look at the whole ecosystem of organisms: We can still treat that ecosystem as a self-organizing system, which has a feedback loop (or lots of them) going on.

You can see that we have these constraints that are acting on the whole system: There are selective constraints in the form of selection pressures, and ten there is variation, enabling constraints in the form of variation. And this is how evolution works.

We have basically these opposing forces of variation and selection acting on the same dynamical system at the same time. And this particular relationship is quite interesting.

Because as the system cycles through its iterations, as it evolves over time, it constantly oscillates between more variance and more selection. Sometimes there are extinction events, whole categories of organisms die out. And sometimes there are these moments when there is a lot of flourishing and a lot of variety starts to emerge. It’s always a back and forth.

Through this process, through this oscillation between variance and selection, at the same time organisms become more adapted to their environment. Of course, in evolutionary time scales that takes a long time and one iteration takes very very long. But you can see the process or the mechanism that’s at work here.

The organisms become more adapted to their environment. Their fitness is optimized. They are basically designed to fit better into their environment, but without the need for an intelligent designer.

Adapted design emerges out of this adaptive process.

There is no desired end-state — "the design".

There is no intelligent designer here, who would determine this end state.

There is just continuous adaptation that causes fitness to be optimized, that leads to better design.

I think if we as makers consider ourselves less as intelligent designers who determine a desired end-state, but more as participants in reciprocal realization with our environment, I think then Alexander's fundamental process starts to look a lot like evolution.

Opponent processing

I want to highlight the importance of the opponent processing that's happening here.

Variation and selection both independently constrain the system. They are fundamentally opposed to each other, they are in opposition to each other. One of them is constantly trying to open up the system, where the other is constantly trying to close down the system.

You don't really want either of those sides to "win". Each of them wins smaller battles, so sometimes there situations with more variation and sometimes there is more selection, but you don't want either side to win the whole war. Because when that happens, the system stops. The system dies.

As long as these opposing forces keep acting against each other through the system, the system keeps going and this leads to this progress of the organisms adapting within this — the system stays alive and there is progress, there is adaptation, there is fitness.

This is another example where we transcend polarization with integration. We can clearly differentiate these two opposing processes, and we can look at them individually and understand them independently.

But when we integrate them into this dynamical system, when they act on the same system, we notice that as long as this eternal conflict stays in place, the system stays alive, it keeps iterating, and the organisms that are part of it become better adapted to their environment.

Again, it's an endless journey of becoming, where it's all about the journey and not at all the destination.

And we get to be part of that journey. That’s the great part.

And it's up to us to decide, if we want to take control over it, or if we want to participate in it.

Up until this point I was primarily trying to show you that we can clearly differentiate between these four things, if we want to, but we can also integrate them.

If we can change our perspective to see how knowing can be a lot like being, and how making is a lot like becoming, we are making big steps towards building beauty and creating wholeness.

V. Meaning

Now, finally I want to connect this to meaning.

What is meaning?

First of all, meaning is a metaphor. We make sense of sentences, when sentences make sense… There is something in our lives ideally, that makes sense in a similar way to how sentences make sense to us.

Meaning is based on our mind’s capacity to form mental representations about the world and develop connections between those representations. Meaning is essentially about connecting things mentally.

It is about forming relevant connections to things, to events, to relationships. It is about bridging this fundamental divide that we experience between objective reality and subjective experience. If we find relevant connections between them, this is when we experience meaning.

Meaning of life?

What kind of meaning am I talking about here? Is it the meaning of life? Am I suggesting that I know what that is? No, I have absolutely no idea what the meaning of life is. Probably something philosophical, metaphysical. But this is not what I’m talking about.

Meaning in life

I’m talking about meaning in life. This turns out to be something that has been studied extensively, because we can ask people the question:

What makes us experience meaningfulness in life?

And turns out a lot of scientists have done that. I’m just giving you a very quick summary here of what scientists find out about this is that apparently we need three things for experiencing meaningfulness:

We need to be able to comprehend the world around us. We need to have some sort of, perhaps scientific, but some sort of understanding. It needs to make sense to us.

We need to find direction for our actions.

We need to find our lives valuable, there needs to be worth in what we’re doing.

It basically boils down to these three things.

Coherence is about understanding — things need to be intelligible to you, your life needs to make sense to you.

Then you need motivation, you need purpose, some sense of direction; you want to have goals and direction in life.

And ultimately you also want significance. This is about evaluation — you want your life to be worth living, so it needs to be good, important in some kind of way.

We experience deep meaning in life, deep fulfillment, when we have all three of those things.

This got me thinking:

If you think of coherence for a moment: When we go to Alexander, he says that things which have life have this dense and complex Indra's Net kind of structure. All the centers are connected to every other center, but it doesn't overwhelm us. It’s not chaotic, it’s very very ordered. We can still make sense of them, because the familiar patterns of the 15 properties for instance, they make even such a complex thing intelligible to us, without over-simplifying them. They are still very complex and there is a lot going on, but they are intelligible to us, we can make sense of them.

If you think about purpose: Centers shape possibilities, future activities. Think of this courtyard which Alexander describes I think in book 2. Where he describes all the activities that can happen in this courtyard, compared to this other Russian apartment building I think, where there’s not much going on. In this courtyard there are all these activities that are made possible by the architecture of that place. Things with life also have these dense patterns of function, but they are not compromising on that function, they are still very effective for all those things, they are not diminishing the experience to support more function. All the functions supported are supported in a deep way. They are fit for multi-apt purpose.

And if you think of significance: Things with life are good, they are relevant, they are important to us. We feel a deep personal connection between them and our selves, in that participatory, being-mode kind of way. I think this is why the Mirror of the Self test ultimately works.

So maybe — and this is just… I mean I’m just making this up… this is just something that I want to offer as a thought experiment — but maybe…

…wholeness is a way of experiencing deep meaning.

Think about it: Things with life…

they make sense to us, they are coherent

they support our projects and goals, they are fit for purpose

and they are good and important, they are significant,

to us, to others, and to the world.

That seems — at least to me — to be what Alexander is pointing towards:

“It is this ongoing rift between the mechanical-material picture of the world (which we accept as true) and our intuitions about self and spirit (which are intuitively clear but scientifically vague) that has destroyed our architecture. It is destroying us, too.

It has destroyed our sense of self-worth.

It has destroyed our belief in ourselves.

It has destroyed us and our architecture, ultimately, by forcing a collapse of meaning.”— Christopher Alexander

References

Alexander, C. (2004) The nature of order: An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe. Berkeley, Calif: Center for Environmental Structure.

Fromm, E. (1976) To have or to be? New York, N.Y, etc. : Harper & Row.

Juarrero, A. (1998) “Causality as constraint,” Evolutionary Systems, pp. 233–242. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-1510-2_17.

Juarrero, A. (2002) “Complex dynamical systems and the problems of identity,” Emergence, 4(1), pp. 94–104. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327000em041&2-09.

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (2017) Metaphors we live by. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Martela, F. and Steger, M.F. (2016) “The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance,” The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), pp. 531–545. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623.

Vervaeke, J. and Ferraro, L. (2012) “Relevance, meaning and the cognitive science of Wisdom,” The Scientific Study of Personal Wisdom, pp. 21–51. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9231-1_2.

Vervaeke, J. and Ferraro, L. (2013) “Relevance realization and the Neurodynamics and neuroconnectivity of general intelligence,” SmartData, pp. 57–68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6409-9_6.

Vervaeke, J., Lillicrap, T.P. and Richards, B.A. (2009) “Relevance realization and the emerging framework in Cognitive Science,” Journal of Logic and Computation, 22(1), pp. 79–99. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/logcom/exp067.

Mirror of the Self is a weekly newsletter series trying to explain the connection between creators and their creations, and analyze the process of crafting beautiful objects, products, and art.

Using recent works of cognitive scientist John Vervaeke and design theorist Christopher Alexander, we embark on a journey to find out what enables us to create meaningful things that inspire awe and wonder in the people that know, use, and love them.

If you are new to this series, start here: 01 • A secular definition of sacredness.

Overview and synopsis of articles 01-13: Previously… — A Recap.

Overview and synopsis of articles 14-26: Previously… — recap #2.

Interesting take. Thanks Stef.